- Home

- Discover

- Visit

- About us

-

-

About Blackdown Hills National Landscape

-

-

-

- Our work

-

-

Our work

-

-

-

- Completed Projects

- ELMS Tests and Trials

- Blackdown Hills Natural Futures

- Catchment Communities Conference

- Corry and Coly Natural Flood Management

- Culm Community Crayfish project

- Culm Enhancement Project

- Discovering Dunkeswell Abbey

- Dunkeswell War Stories

- Field boundaries & linear landscape features

- Nature and Wellbeing

- Metal Makers

- Somerset Nature Connections

- Woods for Water

- Completed Projects

-

- Get involved

- News & social

- Home

- Discover

- Visit

- About us

-

-

About Blackdown Hills National Landscape

-

-

-

- Our work

-

-

Our work

-

-

-

- Completed Projects

- ELMS Tests and Trials

- Blackdown Hills Natural Futures

- Catchment Communities Conference

- Corry and Coly Natural Flood Management

- Culm Community Crayfish project

- Culm Enhancement Project

- Discovering Dunkeswell Abbey

- Dunkeswell War Stories

- Field boundaries & linear landscape features

- Nature and Wellbeing

- Metal Makers

- Somerset Nature Connections

- Woods for Water

- Completed Projects

-

- Get involved

- News & social

Chapter 4: Place

Chapter 4: Place

Published: Oct 2025

Blackdown Hills National Landscape Management Plan 2025-2030

Chapter 4: Place

It is the diverse landscapes, the distinctive villages, the historic and natural environment, that give the Blackdown Hills its special sense of place.

This section of the management plan focuses on sustainable, regenerative and resilient land use and land management that is central to conserving and enhancing the natural beauty of the area. It covers landscape, natural resources and natural capital, farming, forestry and land management, historic environment and geology, planning, development and infrastructure.

In this chapter:

4.1 Objectives – Place

- To restore, conserve and enhance the natural capital stock of the Blackdown Hills National Landscape and maximise the flow of ecosystem goods and services it provides.

- To support sustainable farming, forestry and land management practices that conserve and enhance the special qualities of the Blackdown Hills National Landscape and deliver a range of ecosystem services.

- To strengthen the Blackdown Hills special sense of place, with a diversity of landscape patterns and pictures, unique geology, archaeology, and buildings of architectural appeal, through sound custodianship.

4.2 Guiding principles – Place

- The distinctive character and special qualities of the Blackdown Hills need to be recognised, understood and valued if natural beauty is to be conserved, enhanced and restored.

- Our historic environment and cultural heritage, from its archaeological sites and historic buildings through to the unique arts and crafts produced today, is recognised as an intrinsic part of the landscape and special qualities of the Blackdown Hills.

- We need to ensure that any development and infrastructure affecting the National Landscape is of the highest quality; sensitive to landscape setting and historic character, conserving and enhancing wildlife and other special qualities.

- All those whose actions affect the landscape work together to allow nature and natural processes to thrive, as a foundation of a productive, healthy rural economy.

- Soil health is restored and nurtured; rivers and streams flow clean and other ecosystem services are provided to society as a result of regenerative land management.

- When contributing to meeting national targets, we will be mindful of primarily seeking to maximise outcomes relevant to the opportunities and needs of the Blackdown Hills.

4.3 Targets – Place

These are the Protected Landscapes Targets and Outcomes Framework targets that we will contribute to:

Target 5

“Ensuring at least 65% to 80% of land managers adopt nature friendly farming on at least 10% to 15% of their land by 2030”.

Target 8

“Increase tree canopy and woodland cover (combined) by 3% of total land area in Protected Landscapes by 2050 (from 2022 baseline)”.

Applying the 3% target to the Blackdown Hills National Landscape would be an increase of 1,108 hectares (2738 acres). Therefore, 39.6 hectares (97.8acres) per year between 2022 and 2050, bringing the total amount of woodland to 9,302.93 hectares (22,988 acres).

Target 10

“Decrease the number of nationally designated heritage assets at risk in Protected Landscapes”.

4.4 At a glance – Place

Headlines from State of the National Landscape report 2023:

- Satellite images suggest that there is very little light pollution in the Blackdown Hills National Landscape. There has been a noticeable increase of light spillage from Chard and Taunton areas, and increasing spillage from some communities within the area, noticeably Dunkeswell, Hemyock and around Yarcombe.

- National noise mapping suggests that the extent of traffic noise from major roads is limited in the Blackdown Hills National Landscape. The most recent data is for 2017.

- Particulate matter (PM2-5) levels low in the area but with a hotspot around Hemyock.

- Sulphur dioxide (SO2) levels are low in the area but with hotspots at Hemyock, Dunkeswell and near to Axminster.

- Surface water flood risk is low for most of the area.

- There are 770 Listed Buildings and 26 Scheduled Monuments. Of these, seven assets are at risk (2022); this is a minor improvement since 2019.

- There are ten Conservation Areas within the National Landscape. None are deemed as at risk.

- 78% of the National Landscape is under agriculture (2021).

- During the ten years to 2021 the number of farm holdings has remained at around 625.

- 42% of farms are less than 20 hectares in size and 44% are between 20-100 hectares in size.

- 48% of farms are recorded as lowland livestock grazing.

- Livestock numbers include; Poultry (1,006,928 animals), a 7% increase since 2016; Sheep (22,573 breeding ewes), a 6% decline since 2016; and Cattle (17,965 animals), with a 5% decline since 2016.

- Land in agri-environment schemes has decreased from 11,793 ha in 2017 (27% of the National Landscape) to 8,246 ha in 2021 (22.8% of the National Landscape).

- The total annual value of agri-environment agreements was £2,113,434 in 2021; up from £1,017,856 in 2017.

- There are eight made (adopted) neighbourhood plans – all in East Devon.

- Approval given for one affordable housing scheme since 2017.

Additional data from Defra:

- The total length of river waterbodies within each status under the Water Framework Directive (WFD) is; 122 km moderate status (19 waterbody catchments); 24km poor status (9 waterbody catchments); 0.8km bad status (2 waterbody catchments)

- There are 4 groundwater bodies with high status under the Water Framework Directive and 3 in poor status.

4.5 Priorities for action – Place

This section sets out what we intend to prioritise and how these actions will contribute to each of our targets (see above).

Priorities for Target 5

- Increase the uptake of appropriate agri-environment scheme (AES) options, aiming for 75%+ uptake of Sustainable Farming Incentive (SFI), to underpin Countryside Stewardship and Landscape Recovery additional take-up (the three components of Environmental Land Management- ELM).

- PLTOF stat 12 indicates that the current uptake of agri-environment schemes (in respect of land that is being actively managed in a sustainable way) is relatively low in the Blackdown Hills National Landscape at 18% (6,800 hectares). The Sustainable Farming Incentive (SFI) agri-environment component includes planning actions, including soil and manure management plans. There is currently a relatively high uptake of these planning actions across the area. However they are excluded from the PLTOF figure above as they do not constitute land that is being actively managed in a sustainable way. There is therefore much work to do to increase the take-up of land that is being actively managed in a sustainable way, as this underpins many of the actions in the Delivery Plan. This will require significant promotion and close working with the land management community, via trusted local advisers, scheme administrators and specialists.

- Support and add value to schemes such as the Luppitt Landscape Recovery project (Landscape Recovery round 2) and the potential expansion of the Upper Axe Landscape Recovery project (round 1), as well as rolling out successful Landscape Recovery type management (large scale, long term environmental land management) to other areas in the Blackdown Hills.

Priorities for Target 8

- Undertake significant new tree planting, including orchards, restore undermanaged woodlands (to promote regeneration), and restore/reestablish ‘trees outside woods’ habitats, including hedgerows and hedgerow trees, seeking an additional 1108.76 hectares of tree canopy and woodland cover by 2050.

- Make significant Environmental Land Management (ELM) investment and provide woodland advisory support for willing landowners (including relevant authorities), while applying the ‘right place right tree’ principles. The Somerset and Devon Tree Strategies will help guide and support this.

Priorities for Target 10

- Review the reasons why the assets are still at risk. As a result of positive management, only three Scheduled Monuments from 26 are considered at risk, compared to eight in 2013, and there is also one Listed Building at risk. This is a very small percentage of the designated heritage assets, however moving towards removing all of them from being at risk should be the goal.

Other priorities

- Step up the action needed to tackle Water Framework Directive (WFD) failures (now referred to as the Water Environment Regulations (WER), linked to drinking water quality and supply (including drought), surface quality and downstream coastal waters. This will involve working with land managers, water industry and other delivery partners. Working with the Regulators and Catchment Sensitive Farming officers, to focus attention on crops grown in ‘high risk’ locations and ensuring compliance with the Farming Rules for Water is important, to tackle the systemic failures of many of the waterbodies in the Blackdown Hills (as elsewhere in the south west).

- Continue to promote, deliver and advocate for ‘mainstreaming’ natural-based solutions as a mechanism to provide resilience to property and infrastructure, both within the Blackdown Hills National Landscape but also, importantly, downstream where major critical infrastructure is at risk from flooding and where building resilience is only possible through upstream interventions. Nature-based solution interventions rely on land managers to collaborate at scale. The Blackdown Hills National Landscape Partnership will play a key role here, to help support, incentivise and deliver. More detail on climate mitigation and adaptation can be found in the Climate section.

- Continue to support the farming and land management community through agricultural transition, via farm facilitation support programmes and by responding to ever-changing agricultural policy and the need/incentives to provide ecosystem services for society, including green finance opportunities such as nutrient credits and Biodiversity Net Gain. The National Landscape Partnership play a key convening, supporting and delivery role here.

- Undertake a desk-based appraisal of the historic environment in the protected landscape area, characterising and quantifying the resource and examining the extent of detailed investigation that has taken place to date. Use the results to identify where the most significant gaps in understanding are and how they can be addressed. The potential opportunities for community heritage and citizen science projects to help fill those gaps will also be identified. The last comprehensive desk-based survey of the historic environment in the Blackdown Hills National Landscape was conducted in 1996. Since then, significant changes and newly available information have brought to light the extent of historic environment features across the landscape. An up-to-date study is an essential tool for strategic decision-making concerning the historic environment.

- Continue to inform and influence planning policy, decisions and implementation through development of additional planning guidance and other tools and mechanisms, working with local planning authorities. Develop a shared understanding of the potential opportunities and effects of measures such as carbon offsetting, nutrient credits and biodiversity net gain in relation to conserving and enhancing natural beauty.

4.6 Policies – Place

Landscape, natural resources and natural capital

PL1 Approach the conservation and enhancement of the National Landscape according to landscape-led principles, based on landscape character, underpinned by a sound understanding of the area’s rich stock of natural and cultural capital assets and its value to society in terms of the flow of goods and services.

PL2 The special qualities, distinctive character and key features of the Blackdown Hills National Landscape will be conserved and enhanced, and opportunities will be sought to strengthen or restore landscape character where landscape features are in poor condition, missing or fragmented.

PL3 Promote a catchment-scale, multiple-benefit, collaborative-based approach to soil conservation and restoration, water quality improvements, reducing flood risk, and improving resilience, based on the Otter, Axe, Culm and Parrett/Tone catchments.

PL4 Approaches to flood risk management and erosion control which work with natural processes, conserve the natural environment and improve biodiversity will be advocated and supported.

Farming, Forestry and Land Management

PL5 A profitable, sustainable and environmentally beneficial farming, forestry and land management sector providing a range of public goods and services will be fostered as one of the principal means of maintaining the special qualities and distinctive landscape of the National Landscape.

PL6 Promote, encourage and support widespread take-up of Environmental Land Management schemes that help conserve and enhance natural beauty and deliver a range of environmental outcomes through sustainable farming and forestry practices.

PL7 Encourage the production and marketing of local food, timber and other agricultural and wood products where these are compatible with the National Landscape and purpose of designation.

PL8 Encourage sensitive management of field boundaries and hedgerow trees, woodlands, orchards and ponds, protect ancient woodland and veteran trees, and restore the original broadleaved character of plantations on ancient woodland sites.

PL9 Encourage well managed woodland creation and expansion that considers both the ecological value and landscape character of a site and surroundings and opportunities for maximising ecosystem services including natural flood management.

PL10 Monitor, manage and mitigate damaging diseases such as ash dieback that have potential to impact negatively on landscape and biodiversity.

PL11 Wider community engagement with the farming and land management sector will be encouraged to enable a deeper understanding and appreciation of the important role played by land managers in maintaining the National Landscape’s special qualities.

Historic environment and geology

PL12 Conserve and enhance the historic built environment and rural heritage assets, support training in traditional heritage skills, and promote the use of Historic Environment Record (HER), historic landscape characterisation and other tools to inform projects, policymaking and management activities.

PL13 Monitor the extent and condition of historic sites, features and landscapes across the Blackdown Hills and seek to address sites and features in poor and declining condition.

PL14 Promote awareness and understanding of the geology and geomorphology of the Blackdown Hills and secure effective management of important features and sites.

Planning, development and infrastructure

PL15 All relevant strategic, local and neighbourhood plan documents and planning decision-making will:

- Seek to further the conservation and enhancement of the National Landscape.

- Utilise the Management Plan and consider other Blackdown Hills statements and guidance.

- Ensure that conserving and enhancing landscape and scenic beauty is given great weight.

PL16 All development affecting the Blackdown Hills National Landscape should conserve and enhance natural beauty and special qualities by:

- Respecting landscape character, settlement patterns and local character of the built environment.

- Being sensitively sited and of appropriate scale.

- Reinforcing local distinctiveness.

- Seeking to protect and enhance natural features and biodiversity.

PL17 Promote and protect tranquillity and dark skies by minimising intrusive noise and development and light pollution that may undermine the intrinsic character of the National Landscape.

PL18 The character of skylines and open views into, within and out of the National Landscape will be protected and enhanced.

PL19 The deeply rural character of much of the land adjoining the National Landscape boundary forms an essential setting for the Blackdown Hills and care will be taken to maintain its quality and character.

PL20 Community-led planning tools, such as neighbourhood plans, and initiatives such as Community Land Trusts will be supported as the principal means of identifying need and securing local community assets such as affordable housing. Any development should conserve and enhance natural beauty.

PL21 Road and transport schemes (including design, maintenance, signage, landscaping and safety measures) affecting the National Landscape will be undertaken in a manner that is sensitive and appropriate to landscape character and special qualities, seeking to further the purpose of designation. The landscape, biodiversity and cultural features of the area’s road network such as hedge banks, flower-rich verges, and locally distinctive historic highway furniture, will be protected, conserved and enhanced.

4.7 Context – Place

4.7.1 Natural Capital and ecosystem goods and services

Restoring a good quality and condition of the natural and cultural capital stock (including land, soils, air and water) is the key to the outstanding environment of the Blackdown Hills, as well as delivering a range of multiple benefits and ecosystem services for society (further details are included in the Special Qualities appendix). For example, some of the rivers that rise in the Blackdown Hills provide domestic drinking water for both Devon and Somerset. The River Otter flows across the top of a large ground water aquifer and is a priority for tackling pollution and improving water quality for drinking water through initiatives such as South West Water and partners’ Upstream Thinking project. There are a considerable number of properties in the Blackdown Hills that are not connected to mains water, and therefore rely on water from springs, boreholes and wells. These can be particularly sensitive to rainfall and drought, over abstraction by other users, water quality and contamination risks, which all require consideration.

Water resources

The Blackdown Hills forms part of the headwaters of the rivers Culm, Yarty (running to the River Axe), Otter and Tone/Parrett. People well outside the National Landscape are therefore affected by how land is managed for flood risk and water quality. The rivers that originate in the National Landscape flow downstream through larger towns and villages outside of the National Landscape which are more prone to flooding. As such, land management in the upper river valleys can play a key role in helping to reduce flood risk downstream. A prime example of this is the effect that the river Culm has on the peak flows running through Exeter, as the timing of the river Culm and river Exe peak flows can align, leading to overtopping and flooding of settlements, the M5 motorway and the main railway line. Connecting the Culm is a long term, multi-agency approach to tackling some of the issues in the river corridor and focusing on nature-based solutions to address them. Natural flood management works with natural processes to ‘slow the flow’ of flood waters. This helps to reduce the maximum water height of a flood (the ‘flood peak’) and/or delay the arrival of the flood peak downstream, increasing the time available to prepare for floods. Managing the natural resources of the Blackdown Hills (including mires that act as natural sponges and woodland planting in appropriate locations), sustainable drainage systems, and ecological river restoration projects are important components of natural flood management.

Water quality

Water quality is an essential driver of a thriving and resilient natural landscape full of nature, but it is widely accepted that some wastewater and land management practices in water catchments are increasing nutrient loadings, storm water runoff rates, siltation and pollution incidents that are impacting downstream. The knock-on consequences can have much wider implications, as exemplified by the requirement for new development not to cause increased nutrient pollution to certain protected sites (locally the river Axe SAC and Somerset Levels and Moors Ramsar site), which has caused significant delays to development proposals in the last few years. Diffuse and point pollution and nutrient enrichment are factors affecting water quality in the National Landscape and beyond. Indeed, pollution from rural areas is a significant factor in causing poor water quality in every catchment in the South West river basin district: phosphorus in rivers and sediment from agriculture are particular issues in the East Devon catchment. The Water Framework Directive (WFD) Regulations are an important mechanism for assessing and managing the water environment in the UK and has the core aim of protecting the water environments by preventing their deterioration and improving their quality. It does this by setting ecological targets (‘good’ status for all water bodies) and environmental objectives.

Addressing these issues and improving the water quality in the rivers and waterbodies of the Blackdown Hills is key. There are continuing and new initiatives that offer practical solutions and targeted support such as the Catchment Sensitive Farming programme operate across all the catchments. There is significant community interest in local water quality and initiatives to address the health of our rivers, see Making Rivers Better for example, and the Rivers Run Through Us project.

Parts of the eastern and western fringes of the National Landscape are within Nitrate Vulnerable Zones, where there are controls on some farming activities, particularly relating to manure and fertilisers, to tackle nitrate loss from agriculture. Northern parts of the National Landscape are within a Drinking Water Safeguard Zone (Surface Water), where actions may be required to avoid deterioration in quality of drinking water supplies.

Air quality

The State of the National Landscape report indicates some relative hotspots for different forms of air pollutants, the reasons for which need further appraisal. However, it is the case that agriculture is a significant source of ammonia, mainly arising from diary, pig and poultry units, which are found throughout the Blackdown Hills. Ammonia can drift onto protected sites (SSSIs, etc) and sensitive habitats and add to nitrogen-based nutrient loads. Some Lichen species present in woodlands of the Blackdown Hills are especially sensitive to air pollution. Catchment Sensitive Farming is the main action to deliver reduction in ammonia emissions in agriculture.

4.7.2 Landscape

It is the diverse landscape, the distinctive villages, the historic environment and the tranquil rural setting that combine to give the Blackdown Hills its special sense of place.

Landscape character

Our landscapes have evolved over time, and they will continue to evolve – change is a constant, but outcomes vary. The management of change is essential to ensure that we achieve sustainable outcomes – social, environmental and economic – without losing the inherent valued character. Decision makers need to understand the baseline and the implications of their decisions for that baseline. The process of Landscape Character Assessment has an important role to play in managing and guiding change.

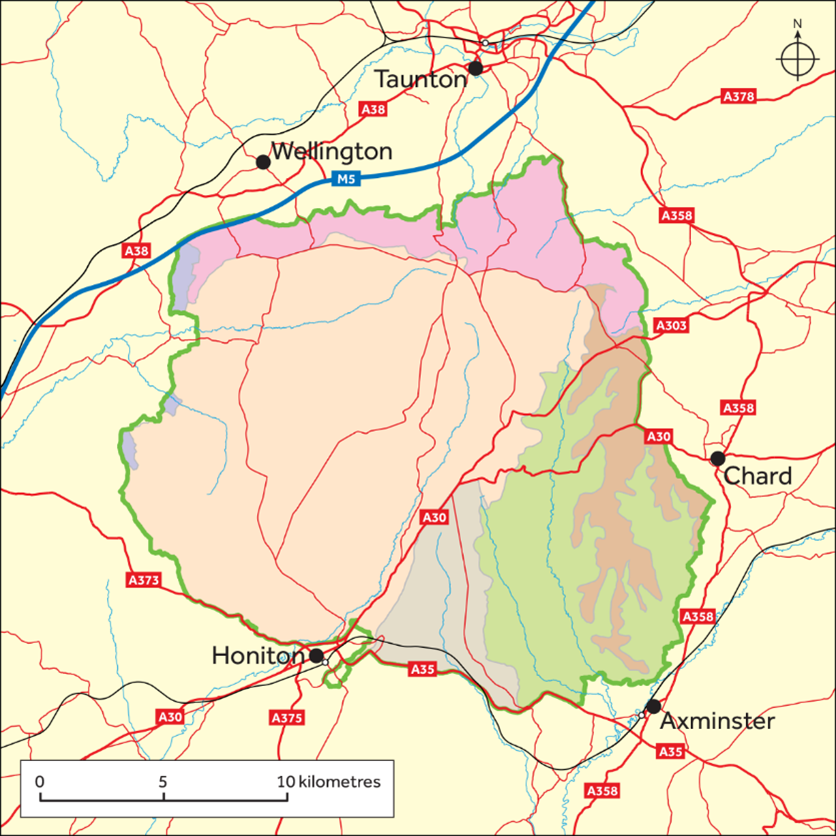

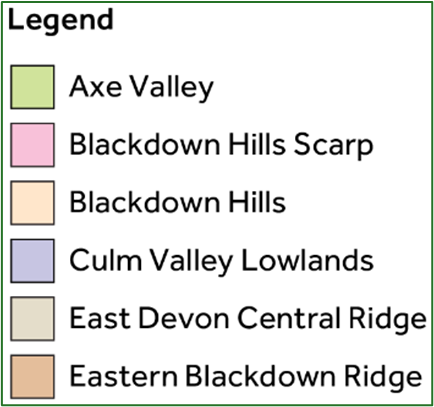

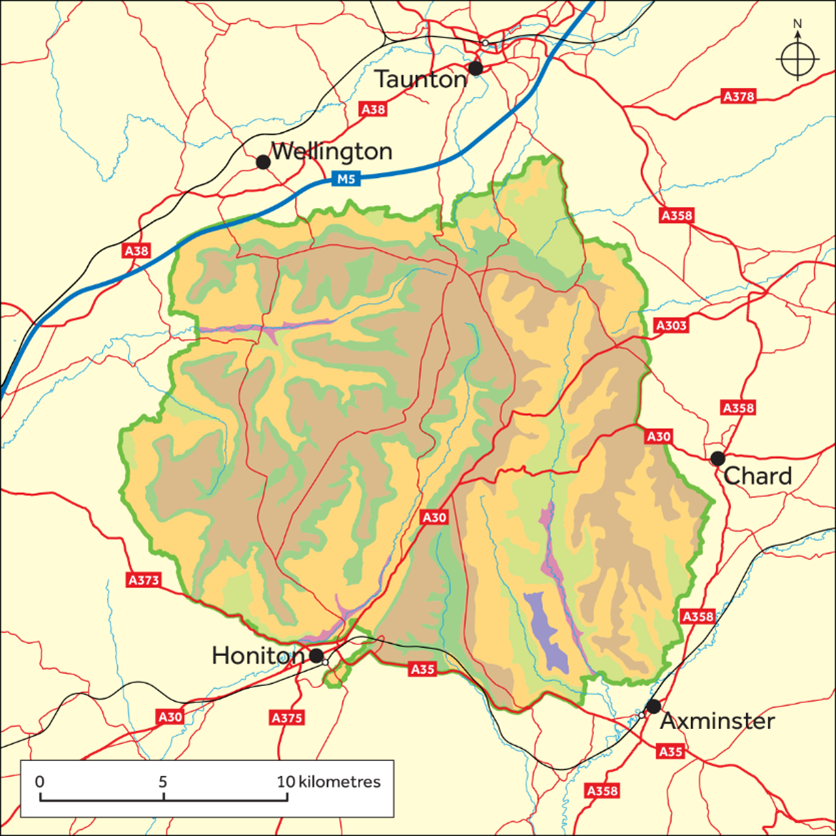

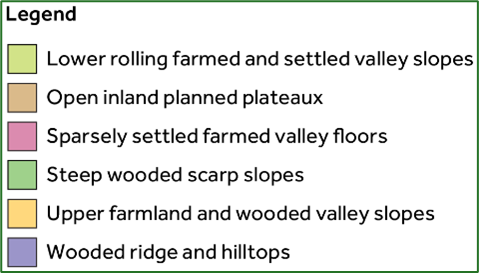

Landscape character describes the qualities and features that make a place distinctive. It can represent an area larger than the National Landscape or focus on a very specific location. The Blackdown Hills National Landscape displays a variety of landscape character within a relatively small, distinct area. These local variations in character within the National Landscape are articulated through the Devon-wide Landscape Character Assessment (LCA), which describes the variations in character between different areas and types of landscape in the county and covers the entire National Landscape. There are Devon Character Areas, named to an area sharing a unique and distinct identity recognisable on a county scale and Landscape Character Types (LCTs), each sharing similar characteristics. Hidden characteristics and past land uses are identified in county-based Historic Landscape Characterisation (HLC).

These assessments should be used in planning and land management to understand and describe the landscape and manage pressures for change and are central to a landscape-led approach in planning and design. Under this approach plans, policies and proposals are strongly informed by understanding the essential character of the site and its landscape context and creates development which is locally distinctive, responds to local character and fits well into its environment; it needs to conserve and enhance the natural beauty, wildlife and cultural heritage of the area and create sustainable and successful places for people.

Further information about the assessments that cover the National Landscape, descriptive information about the character areas and character types relevant to the Blackdown Hills and links to associated documents can be found in an accompanying Landscape Character Assessment summary.

One of the special qualities of the Blackdown Hills National Landscape is its visual relationship with other landscapes and in particular the view of the steep escarpment of the Blackdown Hills rising out of the Vale of Taunton. The wooded edge to the plateau provides a relatively wild, uninhabited backdrop to the flatter, low-lying farmed and settled Vale. The juxtaposition of these contrasting characters means that one enhances the other. The Wellington Monument provides a single focus to the scene and enriches the cultural history of this landscape. This scenery can be appreciated from much of the Vale but makes for dramatic views from southern slopes of the Quantock Hills National Landscape and the eastern fringes of Exmoor National Park. There are expansive and far-reaching views from the Blackdown Hills across much of Devon and Somerset, including views to Dartmoor from Culmstock Beacon and the Jurassic coast from Hembury Hillfort.

The distinctiveness of the Blackdown Hills includes the area’s relative remoteness, timelessness, and tranquillity. Its very character relies on retaining a natural feeling without being over managed. Although hard to quantify it is all too easily lost through, for example, increasing standardisation and suburbanisation, changing agricultural practices and loss of distinctive elements of the natural and historic environment. Each individual case may not have a significant impact, but cumulatively they can erode the area’s distinctive character.

Dark, expansive starry skies are one of the sights which make the Blackdown Hills so special. Night-time darkness is a key characteristic of the area’s sense of tranquillity and relative remoteness. The Blackdown Hills is the fifth darkest National Landscape in England, with very low levels of night-time brightness; 95% of the area is in the two very darkest categories as evidenced by 2016 research by CPRE.

Setting

The setting of a National Landscape is the surroundings in which the influence of the area is experienced. Put another way, it is the area within which development and land management proposals (by virtue of their nature, size, scale, siting, materials or design) may have an impact, be it positive or negative, on the natural beauty and special qualities of the protected landscape. If the quality of the setting declines, then the appreciation and enjoyment of the National Landscape diminishes. Large scale development, the construction of high or expansive structures, or a change generating movement, noise, intrusion from artificial lighting, or other disturbance will adversely affect the setting. Views are one element of setting, associated with the visual experience and aesthetic appreciation. Views are particularly important to the Blackdown Hills. This is because of the juxtaposition of high and low ground and the fact that recreational users value them. Without husbandry and management, views within, across, from and to the National Landscape may be lost or degraded.

4.7.3 Heritage and geology

In the Blackdown Hills National Landscape there is a very strong link between geology, archaeology and the modern landscape. The area retains a strong sense of continuity with the past and the landscape has great time depth, from prehistoric through to modern. Centuries of human activity have created the intricate patterns of woods, heaths and fields, lanes and trackways, and hamlets and villages that contribute greatly to the National Landscape’s unique historic character. More information can be found in the Special Qualities appendix.

Designated heritage assets include 770 Listed Buildings (13 Grade I, 47 Grade II* and 710 Grade II), which is up from 762 in 2013. As a result of positive management, only three Scheduled Monuments from 26 are considered at risk, compared to eight in 2013, and there is also one Listed Building at risk. Understanding and addressing the reasons for these assets being at risk is key to meeting the relevant target in the Protected Landscapes Targets and Outcomes Framework.

The designated heritage resource is only a tiny fraction of the overall heritage assets that combine to form the essential character of the landscape. Over 8,000 sites and buildings of archaeological and historic interest are recorded within the National Landscape on the Devon and Somerset Historic Environment Records (HERs). No information is currently available about the condition of this vast majority of the heritage resource and there has been no thorough assessment of the character of this resource and the level of understanding of it. There is therefore no firm basis upon which to formulate a historic environment research agenda for the area.

The geology of the Blackdown Hills is dominated by one of the finest and most extensive plateaux in Britain – the East Devon plateau – dissected by the long, deep valleys of the rivers Culm, Otter, Yarty, and their tributaries.

Below the surface are near horizontal beds of soft rocks deposited one on top of the other, the youngest at the top. The lower layer, exposed in the river valleys, is marl (red Mercia Mudstone), replaced with Lias in the east. A 30-metre layer of Upper Greensand rests upon this, outcropping as an abrupt rim to the valleys and capping the conspicuous northern scarp slope. Water percolating through the Upper Greensand meets the impervious underlying clay then bleeds out to form springline mires, so characteristic of the Blackdown Hills, that in turn give rise to the headwaters of several river catchments. The composition of Upper Greensand layer, which underlies much of the East Devon plateau, is unique in Britain. This is covered by a superficial deposit of Clay-with-flints-and-cherts.

At the junction of the greensand and clay iron ores were found, and iron production is thought to have started in the Iron Age, through the Roman period and continuing to Medieval time. There is evidence of a Roman clay industry and the chert-tempered local clay supported a medieval pottery industry around the Membury/Axminster area and later in Hemyock, while the almost indestructible chert is used extensively for buildings and walls. On the western edge of the Blackdown Hills the Upper Greensand produced well-preserved fossils, and the area around Kentisbeare and Broadhembury was famed for its whetstone industry in the 18th and 19th centuries. The Blackdown Hills National Landscape has two geological SSSIs covering 3.5ha – Furley Chalk Pit and Reed’s Farm Pit, which are both in unfavourable condition.

The Blackdown Hills National Landscape is significant for its geology and geomorphology with some features unique to the area. The geology influences the landscape, soils and biodiversity and has played a significant role in the area’s industry and heritage. It is vital that this geological resource is protected, conserved, enhanced, promoted, and better understood. Exploration and research into the geology of the National Landscape should be continued to improve understanding of the landscape, and of the geological resource and its importance to inform the conservation and management of geological sites.

4.7.4 Farming and land management

Farmers and land managers are the main stewards of the landscape, and their actions which help maintain natural beauty and the special qualities of the National Landscape should be supported. The farmed area reflects centuries of land management practices and traditions which remain at the heart of our rural communities, producing high quality food, maintaining and shaping the landscape. Farming has a key role to play in protecting the environment by keeping air and rivers clean, improving soils and providing wildlife habitats.

The agricultural sector is in a period of major change especially funding and market uncertainties while arrangements for post Brexit environmental land management system is still developing. Broadly, existing government direct payments to farmers are being phased out and a new system will recognise and value broader societal benefits with payments being based on the provision of public goods, including carbon storage and nature recovery.

Farmers are under increasing pressure to respond to many factors that are influencing the way they use and manage land. Key challenges and changes in agriculture have implications for conserving and enhancing natural beauty.

The number of small family farms are declining and there is an on-going trend towards the amalgamation of farm units and the separation of farmhouse from the land. Thus, farming is being concentrated on fewer, larger, sometimes dispersed units, while many farms are becoming essentially residential, for keeping horses or as small holdings. This risks not only reducing the opportunity for younger people to enter farming but also can lead to the countryside taking on a more suburban appearance. On the other hand, new land managers can bring new opportunities, resources, and ideas that conserve and enhance the natural beauty. Contract labour is used more, often using larger vehicles and machinery and travelling between properties, which can have a wider landscape impact as these vehicles can easily damage the verges and banks of narrow Blackdown Hills lanes and lead to pressure to widen field gateways. The pattern of land management may also change as farmers seek new, profitable activities and markets, including green finance opportunities. To boost profitability especially for dairy farms, there is a shift towards robotic milking, large livestock sheds and zero grazing (animals kept indoors all year). Forage crops that provide high protein/ high volume (such as maize) can be favoured that can result in more compacted soils, risk of runoff from bare soils on slopes and removal of permanent grassland. New crops for energy generation (such as anaerobic digestion) are also a driver for change, while use for recreation or tourism activities is sought on other land.

Soils

Soils are one of the most valuable natural resources we have. Healthy soil supports a range of environmental, economic, and societal benefits. These include food production, climate change mitigation and increased biodiversity. Poor soil management or inappropriate land use can cause soil degradation, which reduces the ability of soil to perform these vital functions. Soil health also underpins the unique character and distinct form of the area’s landscape and biodiversity.

Regenerative agriculture is a suite of practices that put soil health front and centre, allowing farming to be more in tune with nature. As a result, it is seen as a more climate resilient approach to farming whilst also supporting nature recovery. Regenerative agriculture starts with building healthy soil by focusing on rebuilding organic matter and the natural living biodiversity in the soil. This improves the ground’s ability to:

- fix carbon from the air and store it in the soil matrix

- retain and clean water, and reduce flood risk

- Promote soil biology and support wildlife more widely

- recycle nutrients

Regenerative agriculture also delivers on climate change via minimally disturbing soils, which improves soil carbon storage and sequestration, and aids nature recovery from the ground up.

4.7.5 Trees and woodland

There are many reasons why new tree planting is important, at a local and global level, not least in society’s response to climate change, both in terms of increasing offsetting of carbon, and to mitigate the impact of climate change. For example, new planting in strategic locations can reduce the risks of flooding, while planting a diverse range of species can create resilient ecosystems that can cope with changing weather patterns such as prolonged periods of dry weather.

However, careful principles of woodland creation and design objectives are required to maximise the potential benefits and ensure that the woodlands have a strong chance of developing and thriving into the long term. Furthermore, any new planting also has the potential to bring a range of benefits locally and that opportunity should be understood. For example, consideration needs to be given to the suitability of the land to support different woodland types; the surrounding habitats that the new planting could connect with; and the opportunities to work with the local landscape and cultural heritage to deliver multiple benefits, whether nature recovery or public access. As a principle, all new woodland creation and planting schemes should consider the scheme’s impact on landscape, biodiversity and heritage from the outset, following the UK Forestry Standard (UKFS), and utilising the Devon Landscape Character Assessment and Devon’s Right Place Right Tree Guidance (both cover all of the National Landscape). The UKFS, and its supplementary guides, are the basis for sustainable woodland creation and management in the UK.

See also:

- Somerset Tree Strategy

- East Devon Tree, Hedge and Woodland Strategy

- Devon Tree and Woodland Strategy

Both ancient woodlands and veteran trees represent a historic part of the landscape and past land use given they have been undisturbed by development and human activity. Furthermore, they are known to host a diverse array of plants, fungi, birds and insects due to their undisturbed soil and decaying wood, providing optimum growth conditions. They are also a significant carbon store as they have been sequestering atmospheric carbon for centuries. Their support for conservation and climate change mitigation, as well as their status as iconic monuments of our landscape, means ancient woods and veteran trees are widely valued as an irreplaceable resource.

Many woodlands were once managed but recent times have seen a reduction in coppice cutting, the cessation of timber harvesting resulting in a permanently closed canopy, or the planting of ancient woodland with conifer. All of these lead to a decline in biodiversity which can be rectified by the application of sensitive management.

Tree diseases pose an increasing and significant pressure on the natural beauty of the Blackdown Hills, for example ash dieback especially where ash is a dominant tree in and outside woods and/or hedgerow component.

Effective woodland management is essential for growing timber of high value and other wood products such as wood fuel, but it also supports delivery of ecosystem services. Thinning out trees increases their capacity to sequester carbon and enhances their habitat quality as more light is let through. This form of low-intensity management is particularly supportive of good-quality and young-medium age trees which are most efficient at sequestering carbon. Well-managed woodlands also lead to thriving habitats that support wider ecosystems.

In the Blackdown Hills, commercial sustainable timber production, including conifer crops where appropriate to the landscape, has a role to play in sustaining economically viable landholdings that can continue to provide a wide range of ecosystem services. Alternatively, community woodland management schemes, such as Neroche Woodlanders, are encouraging new ways of working woods, as well as bringing a wide range of other benefits from wood fuel to health and wellbeing.

Hedges are an integral, unifying landscape feature of the Blackdown Hills, of historical importance, defining the farmed landscape, and supporting wildlife, while also helping to control soil erosion and reduce flooding. The well-established Blackdown Hills Hedge Association continues to promote the traditional hedge-laying management of hedgerows through training courses, competitions and other events.

4.7.6 Planning and development

Villages, hamlets, farmsteads, individual buildings and their settings form a vital element of the character of the Blackdown Hills. The planning and design of any development, large and small, both within the National Landscape and around it, is of key importance in maintaining the landscape and scenic beauty of the area.

Planning policy

Planning decision-making in the National Landscape is the responsibility of the local authorities within the context of the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) and local development plans, including Neighbourhood Plans. All local authorities and parish councils also have a duty to seek to further the purpose of conserving and enhancing natural beauty in all their actions affecting a National Landscape.

The NPPF provides specific planning guidance for plan-makers and decision-takers in relation to National Landscapes. The latest version was published in December 2024 and confirms that:

- National Landscapes [and National Parks] have the highest status of protection in the planning process.

- great weight should be given to conserving and enhancing their landscape and scenic beauty.

- the scale and extent of development should be limited.

- development within their setting should be sensitively located and designed to avoid or minimise adverse impacts on the designated areas.

- when considering applications for development permission should be refused for major development other than in exceptional circumstances, and where it can be demonstrated that the development is in the public interest (see below and in the appendices).

The NPPF also references the importance of high design standards and materials that reflect the identity of the local built and natural environment. The avoidance and reduction of noise and light pollution are addressed with references to protecting tranquil areas and intrinsically dark landscapes – special qualities of the Blackdown Hills.

Sustainable construction methods offer the potential to reduce the wider environmental impacts; this includes advocating sustainable drainage systems (SuDS), a natural approach to managing drainage in and around development. In the Blackdown Hills National Landscape, where possible, new developments should incorporate sustainable technology, renewable energy sources, and energy and water efficiency as standard; and the use of locally sourced materials, including sustainably grown timber and wood products, should be encouraged. (Also see the Climate section, including policies). However, these need to be balanced with retaining a locally distinctive built environment with a strong local vernacular – special qualities of the area. There may also be implications related to sourcing local materials to be managed, for example extracting building stone.

As evidenced in neighbourhood plans and similar, meeting local housing needs should be the priority for new housing developments in the Blackdown Hills. The availability of a range of affordable housing (as defined in the NPPF), and other more affordable options, is a high priority for many local communities due to the limited choice of accommodation available and lack of affordability. Some have established Community Land Trusts to address provision. Whether on an exceptions site or part of a larger site, great weight should be given to conserving and enhancing landscape and scenic beauty.

Major development

The NPPF does not define the meaning of the phrase ‘major development’ in respect of protected landscapes and there is no single threshold or factor that determines whether a proposal is major development for the purposes of paragraph 190. However, a footnote confirms that is a matter for the decision maker, taking into account its nature, scale and setting, and whether it could have a significant adverse impact on the purposes for which the area has been designated. In the context of the relevant NPPF paragraphs, the potential for harm to the National Landscape should be foremost to the determination of whether development is major or not. This requires consideration of a range of site and development specific factors that include (but are not limited to) location, setting, the quantum of development, duration, permanence or reversibility of effects. Harm to the Blackdown Hills National Landscape is any impact which causes loss, damage or detriment to its natural beauty, its special qualities or its distinctive characteristics or to the perception of natural beauty. There is further information on the consideration of ‘major development’ in the appendices.

Role of the management plan

The Management Plan aims to promote consistency and co-operation between local planning authorities, both in setting policy and dealing with planning applications within the National Landscape, to conserve and enhance natural beauty across the area. Government planning policy guidance explains that management plans help to set out the strategic context for development and provide evidence of the value and special qualities of the area. It goes on to highlight that they may contain information which is relevant when preparing plan policies, or which is a material consideration when assessing planning applications.

The Management Plan provides supporting evidence and complementary policy guidance for local plans and can be referenced to inform development proposals and decisions. The plan is supplemented by topic-specific guidance, such as the Blackdown Hills Design guide for houses and Good lighting guide. It is expected that these will be reviewed and updated, and further design/planning guidance will be prepared during the life of this plan to reflect new agendas and priorities.

Considering natural beauty in planning proposals

It is important that impacts on the Blackdown Hills National Landscape are properly recognised and accounted for in decision making. In an area like the Blackdown Hills where timelessness and escape from the modern world are written into the core qualities underpinning the designation, some degree of harm will inevitably occur as a result of development and needs to be explicitly recognised and assessed. The Management Plan and supporting documents should help planning authorities, developers and land/homeowners understand the landscape’s capacity for change and assess impact. Mitigation is a response to harm, a way of ameliorating but not eliminating impact, and should not be a justification for allowing inappropriate development. A clear understanding of the National Landscape ’s special qualities and distinctive characteristics will help to develop proposals which avoid or minimise harm.

The special qualities and defining characteristics of the Blackdown Hills National Landscape predominantly relate to the distinctive nature of the farmed landscape; the mosaic of land use types and hedges, and the isolated, dispersed type of development much of it driven by the topography of the area, which in turn is a product of the unique geology. Much of the appeal of the area stems from the relatively low level of ‘modern’ development. Essentially what we are considering in the Blackdown Hills are large tracts of an intact historic/cultural farmed landscape. The challenge, therefore, is to seek a sustainable approach to development that respects this inherent character and landscape assets whilst also fostering the social and economic wellbeing of local communities.

The layout, form and density of all new developments need to reflect the historic rural grain of the National Landscape. It is important that all new development, especially housing development, is of a scale and layout that conserves and enhances the distinctive pattern of built form found across the Blackdown Hills, specifically a low density, dispersed pattern of development. Location and context are important considerations and development should:

- Respect the importance of the setting of the National Landscape,

- Respect the importance of the setting of individual settlements, hamlets and historic farmsteads,

- Maintain the existing pattern of fields and lanes,

- Maintain the integrity of the hedgerows and irreplaceable habitats, including ancient woodland, and ancient and veteran trees, as well as open agricultural vistas, and

- Enhance the sense of place.

Development proposals in or affecting the Blackdown Hills should avoid sensitive locations that will impact on the special qualities of the National Landscape – notably views – including prominent locations on the northern scarp slope, on skylines and hilltops, the open plateaux and ridgelines, and undeveloped valley slopes. Attention should be given to noise and activity arising from developments together with lighting to avoid having an adverse impact on the area’s tranquillity and dark skies. This may apply to development some distance from the National Landscape as well as within.

The sense of place is easily lost; suburbanisation and the cumulative effect of ‘permitted development’ break down local distinctiveness; replacing small-scale, locally distinct features with ones of a standard design erodes local character – for example the choice and style of gate, fence, wall or hedge around a house, or pavements, kerbs and driveways in new development.

A major challenge in more rural areas of the Blackdown Hills, agricultural buildings and development are significant issues and can be detrimental to natural beauty if not handled sensitively. As some agricultural practices continue to intensify and with an increasing awareness of animal welfare requirements, the demand for modern large-scale agricultural buildings, which are increasingly taller and larger, at odds with an inherently small-scale landscape, is continuing. To comply with environmental regulations comes large-scale slurry storage facilities often in isolated and elevated locations with associated landscape and visual impacts, and the enclosure of open yards, often infilling the gaps between existing structures resulting in the visual massing of buildings.

4.7.7 Roads and traffic

Inevitably most people in rural areas need a vehicle to access employment, services and other opportunities. Nevertheless, reduction of unnecessary car use will contribute to reducing carbon emissions, quality of life and conservation of the area’s natural beauty. In terms of supporting that shift, the availability of electric vehicle charging points is expanding but is still very limited.

Much of the road network is made up of rural roads and lanes, not built or maintained for the volume, traffic size and use which they now must sustain. The design and management of the rural road network should reinforce the local character and distinctiveness of the Blackdown Hills. The distinctive character of minor roads contributes to the character of the wider landscape, and they are an important means for people to experience the area. Insensitive, overengineered changes to these roads can have a detrimental impact. The increasing use of larger heavy goods vehicles and farm vehicles is having damaging impacts.

Road improvement schemes within and outside the National Landscape should not increase noise pollution or emissions from traffic. Approaches such as speed management schemes may, for example, be more appropriate than road widening. Potential impacts within the Blackdown Hills National Landscape of proposed road improvement schemes beyond the boundary should be considered. Road management and improvement schemes should minimise landscape impact and avoid urbanisation of rural roads – for instance through sensitive and appropriate design and use of materials, and avoiding unnecessary signage clutter, road markings and coloured road surfaces. Wildflower-rich verges should be managed appropriately and traditional features such as fingerposts and milestones should be retained.

Highways England looks after the M5 and A35 trunk road, both which partly bound the Blackdown Hills, and the A303/A30 which passes through the middle of the Blackdown Hills. Other major roads on the periphery are the A373 and A358, which are not part of the national strategic network, and are looked after by the respective county council.

Alterations or improvements to any of the above routes could have an impact on the special qualities and setting of the National Landscape and adversely affect local communities. Full consideration of the environmental and landscape impacts would be required as part of the feasibility and scheme development. Highway authorities and Highways England have a duty to seek to further National Landscape purposes in carrying out their functions.

Meanwhile, national rail services can be accessed at Honiton and Axminster, as well as Taunton and Tiverton Parkway. There are proposals for a new station at Wellington too.

Footer Navigation

Widget

Widget

Widget

Blackdown Hills National Landscape is the new name for Blackdown Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

© 2025 Blackdown Hills AONB